Hilma af Klint

Zoe Beloff

Anne Chu

Jay DeFeo

Emily Dickinson

Harrell Fletcher

Hamish Fulton

Rodney Graham

Susan Howe

Ricky Jay

Paul Lincoln

Allan McCollum & Matt Mullican

Matt Mullican

Max Neuhaus

Maria Nordman

Allen Ruppersberg

Paul Scheerbart

Michael Smith

Robert Walser

Eliot Weinberger

Robert Walser: Looking at Pictures

144 pages with 16 tipped-in full color images

Translated by Susan Bernofsky, Lydia Davis and Christopher Middleton

Introduction by Susan Bernofsky and Christine Burgin

(Christine Burgin/New Directions)

Looking at Pictures presents a little-known facet of the work of Robert Walser (1878-1956):

his writings on art. As a young writer producing prose for publication in journals and newspapers,

Robert Walser frequently devoted his attention to works of visual art. Sometimes these were works by

his brother, Karl Walser, a celebrated stage set designer and painter, sometimes works by those in

his brother's circle but often the work of old masters who Walser greatly admired. The pieces in

this collection include some of his earliest prose as well as work from the final years of his

career. Some of them are fluid meditations on art that touch only tangentially on the paintings that

are their ostensible subjects. Others are meticulous descriptions of works down to their most minute

details. Walser's way of seeing is eminently his own. Something special happens when he is

contemplating a work of art. "A camera," the photographer Dorothea Lange once said,

"is a tool for learning how to see without a camera." We can say something silmilar about

Walser's writings on art. In these stories and essays, art is a tool for learning how to see without

art.

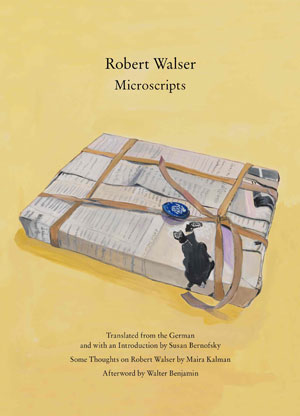

Robert Walser: Microscripts (paperback edition)

160 pages with 43 color and 2 black and white illustrations

with new translations by Susan Bernofsky

and some thoughts on Robert Walser by Maira Kalman

(Christine Burgin/New Directions)

This paperback edition of Walser's Microscripts adds to the original collection (see below) a

handful of microscripts newly translated by Susan Bernofsky including Pencil Sketch in which

Walser describes his special need for writing as he does. This book also publishes for the first

time Maira Kalman's “Thoughts on Robert Walser,” a collection of paintings and texts

created especially for this publication. As Susan Bernofsky notes in her introduction, there is a

special affinity between Walser and Kalman: “Just as Kalman herself paints objects in such a

way as to give an impression of almost infinite, constantly changing signification, Walser too shows

us again and again that ‘We don't need to see anything out of the ordinary. We already see so

much.’”

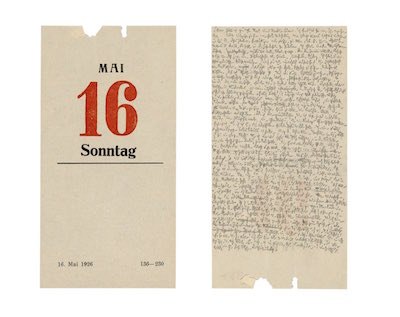

Microscript 337 which measures 5 1/3 x 2 3/4 inches is Robert Walser's original manuscript for

the story Radio, written in May-June 1926 and published in Prager Presse, May 27,

1928.

The following translation by Susan Bernofsky is from Robert Walser: Microscripts.

Radio

Yesterday I used a radio receiver for the first time. This was an agreeable way, I found, to be

convinced that entertainment is readily available. You hear something that is far away, and the

people producing these audible sounds are speaking, as it were, to everyone-in other words they are

completely ignorant as to the number and characteristics of their listeners. Among other things, I

heard the sports results from Berlin. The person announcing them to me had not an inkling of my

listenership or even my existence. I also heard Swiss-German poetry being read, which in part I

found exceptionally amusing. When a group of people listens to the radio, they naturally stop

carrying on conversations. While they are occupied with listening, the art of companionship is, as

it were, neglected a little. This is a quite proper, obvious consequence. I and the people sitting

beside me heard someone playing the cello in England. There was something strange and marvelous

about this.

It would be discourteous to fail to acknowledge straightaway the triumph of the spirit of technical

innovation. How splendid to be enjoying piano music that came dancing up to me from a magical

distance, I found: the music seemed to possess a certain buoyant languor. And now today I find a

director's position advertised in a well-established paper. Thinking back to how someone once, at an

advanced hour of the evening, declared me an out-and-out success - a characterization that by no

means struck me as flattering - I asked myself whether I oughtn't apply for the advertised position.

A leadership post. How odd, the way details of your life from the distant past can suddenly occur to

you, for example this minor incident referring to my status as a "successful person." And

the way I leapt up at once from my seat that night to challenge the one who'd dished up that

expression that struck me as so inappropriate. "You owe me an explanation," I shouted in

his direction. He replied that he had merely wished to express that he considered me an extremely

nice person. Hearing this response, I declared myself satisfied. As for the directorship, energy and

adroitness are demanded of the pool of applicants. A solid general education, the advertisement

said, was the main prerequisite. That I am occupying myself with the question of whether I possess a

sufficient quantity of what is being required here does not particularly surprise me.

Several days ago, by the way, the daughter of a household situated in the best neighborhood in town

asked me: “Would you like it if I were, in future, to address you as 'Robi'?" This question was

posed beside a garden gate, and I believed I was justified in replying in the affirmative. You have

to understand, this directorial advertisement gives me pause, and you will further not find it

incomprehensible for even a moment that I am secretly proud of this question that a member of the

upper crust saw fit to address to me. That I listened to the radio for the first time yesterday

fills me with a feeling of internationality, though I have surely just made a remark that is in no

way modest, by the way.

I am living here in a sort of hospital room, and am using a newspaper to give support to the page on

which I write this sketch.

A Little Ramble: In the Spirit of Robert Walser

160 pages with 50 color illustrations

Contemporary artists respond to the work of Robert Walser.

A project initiated by the Donald Young Gallery including the work of

Fischl/Weiss, Moyra Davey, Thomas Schütte, Rosemarie Trockel, Mark Walllinger, Tacita Dean,

Rodney Graham and Josiah McElheny and a selection of poems and stories by Robert Walser chosen

by the artists.

Afterword by Lynne Cooke

(Christine Burgin/Donald Young Gallery/New Directions)

A Little Ramble: In the Spirit of Robert Walser was initiated by the gallerist Donald Young,

who saw in Robert Walser an exemplary figure through whom connections between art and literature

could be discussed anew. He invited a group of artists to create and exhibit work in response to the

writings of Robert Walser. This book is a result of that collaboration.

A Little Ramble is a Walser reader of material chosen by the artists. There are Walser love

stories discovered by Thomas Schütte in the 70s appearing here for the first time in English,

translated by Susan Bernofsky; the poem Snow which inspired Rosemarie Trockel also newly translated

for this edition by Christopher Middleton; the little known Walser story A Painter's Life

illustrated by Josiah McElheny; Pantoums by Rodney Graham based on the first line of Walser's

Berlin stories and excerpts from Wandering with Walser, conversations with Walser recorded by

his guardian, Carl Seelig, chosen by Moyra Davey to name only a few. Also included in the book is an

afterword by Lynne Cooke and an introduction by Donald Young.

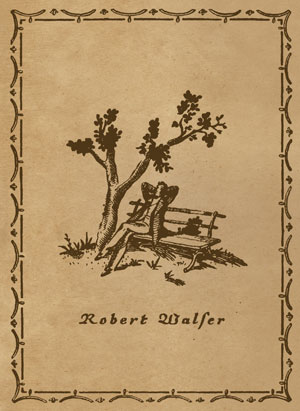

Robert Walser

Thirty Poems

Selected and translated by Christopher Middleton

(Christine Burgin/New Directions)

Cover illustration by Karl Walser for Robert Walser's Kleine Dichtungen 1914

62 pages with 3 color illustrations

In Thirty Poems, renowned translator and poet Christopher Middleton presents a selection of

his favorite Robert Walser poems. Although considered one of the major writers of the early

twentieth century for his novels and short stories, Walser (1878-1956) was essentially a poet. In

his Foreword to Thirty Poems, Christopher Middleton, who first translated Robert Walser in 1957,

illuminates this wonderful but little-known body of work. Facsimiles of poems as they originally

appeared illustrate the book: a manuscript in Walser's perfect Sütterlin script, another

in the almost indecipherably minuscule pencil writing of his microscripts, and also a newspaper

clipping of a poem's original publication in the Prager Presse. Thirty Poems is the

first collection of Walser's poetry in English and includes poems never before translated.

"In one of these beautiful poems, Robert Walser writes that reading ‘made methe happiest

inhabitant of the star they call this earth.’ Read this bookand you too will become that

happy—that happiest—inhabitant."—Francine Prose

"These fresh, spirited poems, in Christopher Middleton's inventive translations, offer us a valuable

counterpart to the bold and idiosyncratic fictions of Walser that we are so fortunate to have

available for our delectation in English already."—Lydia Davis

![Robert Walser | Microscripts [First Edition]](../images/projects/walser/walser_microscripts.jpg)

Robert Walser: Microscripts [First Edition]

Co-published by Christine Burgin and New Directions

Translated by Susan Bernofsky

Afterword by Walter Benjamin

Bilingual

160 pages with 28 color and 28 black and white illustrations

press

release

Born in Switzerland in 1878, Robert Walser worked as a bank clerk, a butler in a castle and an

inventor's assistant while beginning what was to become a prodigious literary career. Between 1899

and his forced hospitalization in 1933 with a now much-disputed diagnosis of schizophrenia, Walser

produced as many as seven novels and more than a thousand short stories and prose pieces. Though he

enjoyed limited popular success during his lifetime, his contemporary admirers included Franz Kafka,

Hermann Hesse, Robert Musil and Walter Benjamin. Today he is acknowledged as one of the most

important and original literary voices of the twentieth century, his work the subject of essays by

W.G. Sebald, J.M. Coetzee, William Gass and Susan Sontag. Describing his own work, Walser wrote: "My

prose pieces are, to my mind, nothing more nor less than parts of a long, plotless, realistic story.

For me, the sketches I produce now and then are shortish or longish chapters of a novel. The novel I

am writing is always the same one, and it might be described as a variously sliced-up or torn-apart

book of myself." In the latter years of his career, Walser struggled with a paralyzing writer's

cramp that he combated by composing his texts in a miniscule pencil script written on small slips of

paper that he carefully cut to size. This handwriting was so small that his guardian Carl Seelig

mistook it for a sort of secret code. After his death in 1956 while out on a solitary walk, a

collection of these papers were found among his belongings and preserved, but many years passed

before they were transcribed and published.

Train Station (II)

Translated by Susan Bernofsky

From Robert Walser: Microscripts

One of the cleverest and most practical technological advances

brought forth by the modern age is, in my opinion, the train station.

Daily, hourly, trains rush either into or out of it, bearing persons of

all ages and characters and of every profession off into the distance

or else whisking them back home. What a life pageant is offered

by this entity I am reporting on here with pleasure, though also

without describing it all too exhaustively, as I am not an expert.

I hope I am justified in observing it instead from a more general,

accessible angle. The very picture the station presents, with all its

comings and goings, can be described as highly agreeable, and to

this must be added all the particularly refreshing and delightful

sounds—he shouts, people talking, the rolling of wheels, and the

reverberation of hurrying footsteps. Here a little lady is selling

newspapers, and over there packages and small valises are being

checked at the baggage counter for such and such a length of time.

Amid the graceful clinking of useful money, train tickets are being

requested and dispensed. A person about to set off on a journey

quickly partakes of a sausage or plate of soup in the restaurant to

fortify himself. In the spacious waiting rooms, male and female

possessors of wanderlust cool their heels, some with a pleasure-filled

jaunt before them, others pursuing serious business objectives

and mercantile or commercial plans aimed at preserving their

subsistence. Books are on display and for sale at a kiosk, including

merely entertaining or suspenseful volumes and high-quality reading

material. You need only reach out your hand for culture and pay

the specified price. Elsewhere you encounter fruits such as apples,

pears, cherries and bananas. Posters inform you of the interesting

sights to be seen all over the world, for example an ancient city,

quays bearing palace hotels, a mountain peak, an imposing cathedral,

or a palm-studded landscape with pyramids. All manner of

things both known and unknown are parading by. I myself am

sometimes well-known, sometimes a stranger. Often entire associations

go marching respect-inducingly through the main hall, a

space that exemplifies the Machine Age and embodies something

international. It's almost romantic to think that in all these countries,

be it in the sunlit daytime or at night, trains are indefatigably

crossing back and forth. What a far-reaching network of civilization

and culture this implies. Organizations that have been created

and institutions that have been called into existence cannot simply

be shrugged off. Everything I achieve and accomplish brings with

it obligations. My activity is superior to me.

It's lovely when a parting takes place at a train station or else a

reunion transpires and occurs.